Future Proof — Angkana Rüland

Published Mar 18, 2020

Angkana Rüland has been a Max-Planck research group leader of the group Rigidity and Flexibility in PDEs at the MPI MiS since October 2017. In joint work with her group she has investigated inverse problems, nonlocal equations, problems from the calculus of variations and free boundary value problems. Before starting at the institute, she studied Mathematics in Bonn and Leipzig and had been a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Oxford. In April 2020 she will become a professor of applied mathematics at the Ruprecht-Karls-University in Heidelberg.

Interview

Why does mathematics fascinate you?

Angkana Rüland: I was always fond of mathematics in school, but could also have imagined studying other subjects at university. When encountering math at the university level, I was fascinated by the clarity of mathematical arguments and the idea of being completely rigorous about a statement. Furthermore, having always been interested in the natural sciences, mathematics was an ideal way to combine precise, rigorous mathematical analysis with working on relevant applications in the natural sciences. The interaction between exciting, new math, which is already significant from an inner-mathematical point of view and in this sense purely curiosity-driven, and its application to problems from the natural sciences is an important source of motivation for me. I love the fact that once a problem is “understood” many more fascinating new problems related to it emerge.

What motivates you in your research?

Angkana Rüland: The curiosity of understanding something new is one of my main sources of motivation. Often, when trying to understand and to “solve” a problem, you run into a multitude of challenges and many ideas do not work the way you had hoped. Of course, this can sometimes be very frustrating. However, learning from these experiences, exploring how far you can push an idea and finding ways out of seemingly dead ends, makes it extremely rewarding when all ingredients suddenly fit together and give a “clear picture” of the situation. Of course my research field is another major motivation for me. I love to work at the interface between mathematics and the sciences and to discuss problems, not only with other mathematicians, but also with engineers and physicists.

Research

Unique continuation and inverse problems

Inverse problems are ubiquitous in nature: Animals like bats navigate with sonar, medical applications like X-ray tomography allow for non-invasive measurements and diagnoses and spectroscopy methods allow to indirectly determine the composition of chemical substances. In all of these examples one is interested in reconstructing information in various settings from physics, engineering or medicine for which only indirect, non-invasive measurements are available. The theory of inverse problems for which unique continuation results yield important tools allows one to deduce such results in a mathematically precise way.

Free boundary value problems and their regularity properties

Free boundary value problems arise in many processes in the sciences and our daily lives. A prototypical example for instance includes the melting of ice in water, the so-called Stefan Problem. While there are evolution equations for the ice and the water, the interface of the ice and the water is not explicitly given in the description of this problem. It is part of the problem to determine, to predict and to analyze its evolution. This makes these problems very “nonlinear” and poses interesting mathematical challenges in particular in terms of the regularity theory of the solutions and interfaces.

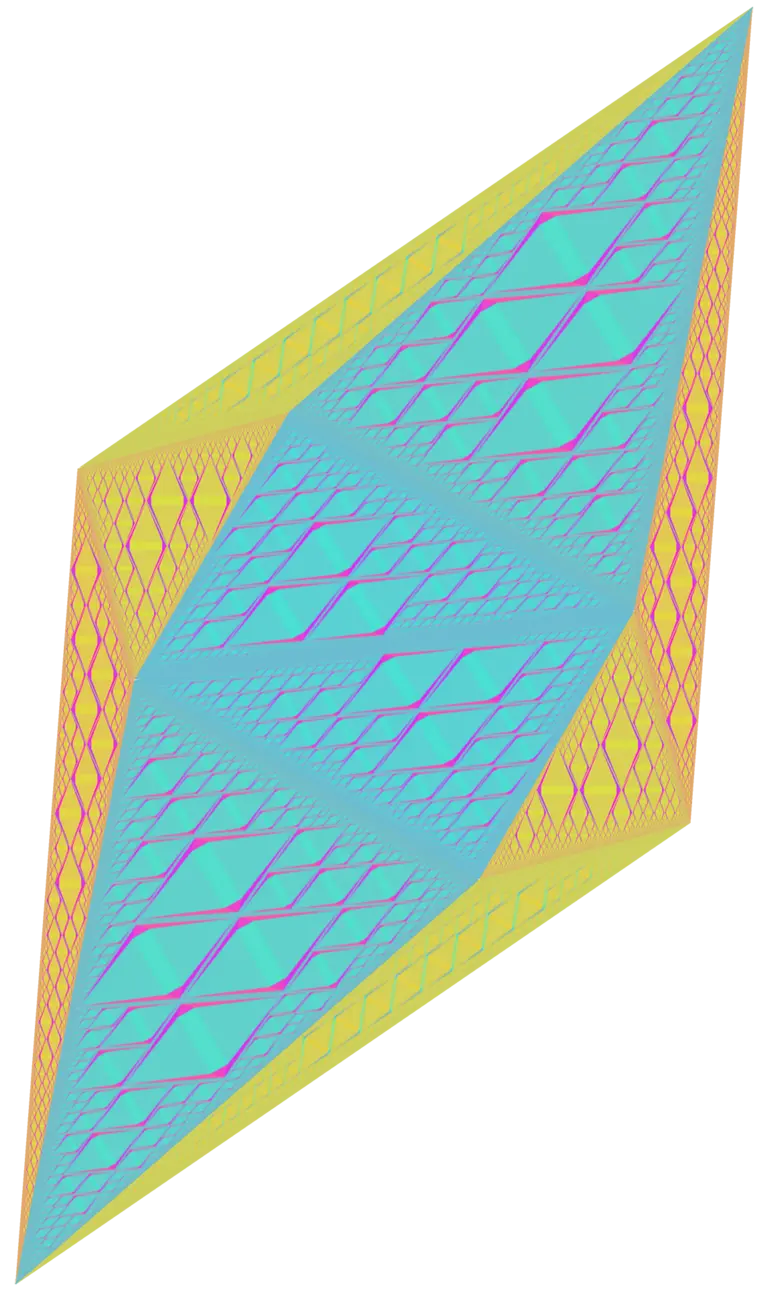

Problems from the calculus of variations in particular the dichotomy between rigidity and flexibility in the modelling of shape-memory alloys

Shape-memory alloys are materials with a thermodynamically very interesting behaviour making them promising materials for a number of industrial applications. Just as in the melting of ice to water, these materials also undergo a phase transformation, however from one solid state with very high symmetry at high temperatures to another solid state with less symmetry at low temperatures. This loss of symmetry implies that the materials have different variants of their low temperature state and are thus very flexible. When heating up the material again, it loses this flexibility and has to recover its original shape – it has “a memory”. Mathematically, the presence of multiple variants of the low energy states provides these materials with a rich energy landscape leading to a variety of different microstructures. It has been one of the objectives of the research group Rigidity and Flexibility in PDEs to study their rigidity and flexibility properties.

Notable Publications

- Angkana Rüland, Mikko Salo, The fractional Calderón problem: low regularity and stability, Nonlinear analysis / A, 193 (2020), 111529.

- Angkana Rüland, Jamie M. Taylor, and Christian Zillinger, Convex integration arisingin the modelling of shape-memory alloys : some remarks on rigidity, flexibility and some numerical implementations, Journal of nonlinear science, 29 (2019) 5, p. 2137–2184.

- Herbert Koch, Angkana Rüland, Wenhui Shi, The Variable Coeffcient Thin Obstacle Problem: Carleman Inequalities, Advances in Mathematics, Vol 301 (2016), pp.820–866.

Scientific Contact

Angkana Rüland

Editorial Contact

Discover More

-

Article

Download the pdf booklet of this Future proof article

Related Content

Future Proof - Samantha Fairchild Future Proof - Samantha Fairchild

Future Proof - Tobias Ried Future Proof - Tobias Ried

Benjamin Gess Appointed as Professor at TU Berlin Benjamin Gess Appointed as Professor at TU Berlin