Viscous Thin Films

Lubrication theory

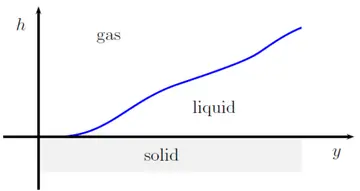

Thin liquid films appear in a variety of situations in nature and in engineering applications. Examples include tear films in the eye, membranes in biophysics, linings in the lungs of animals, or paints. Despite the diversity of phenomena and applications, the mathematical modeling is quite similar if the film is sufficiently viscous. Excluding other contributions such as rotational forces, gravity, or van-der-Waals (molecular) interactions, it is reasonable to assume that the dynamics of the film are only driven by surface tension and viscosity, indicating the gradient-flow structure of the problem. In the regime of thin films, one commonly refers to this approach as lubrication approximation.

The thin-film equation

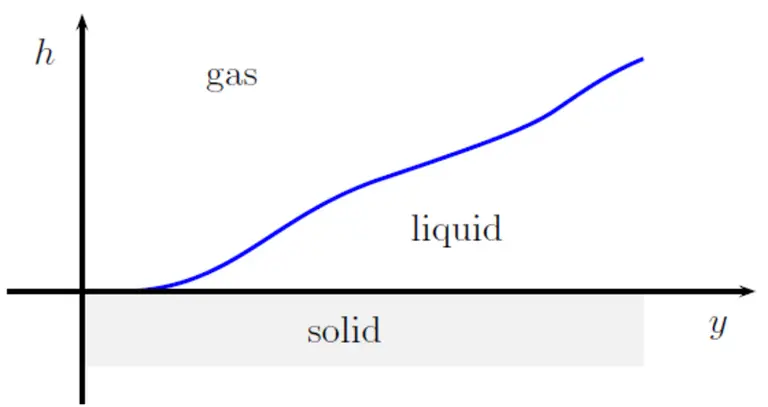

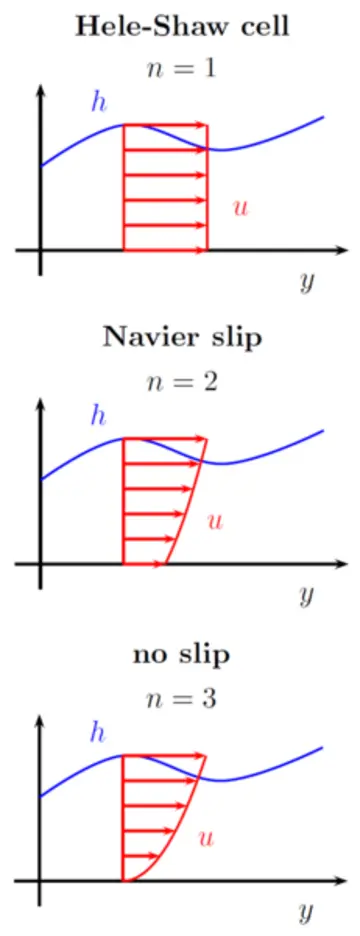

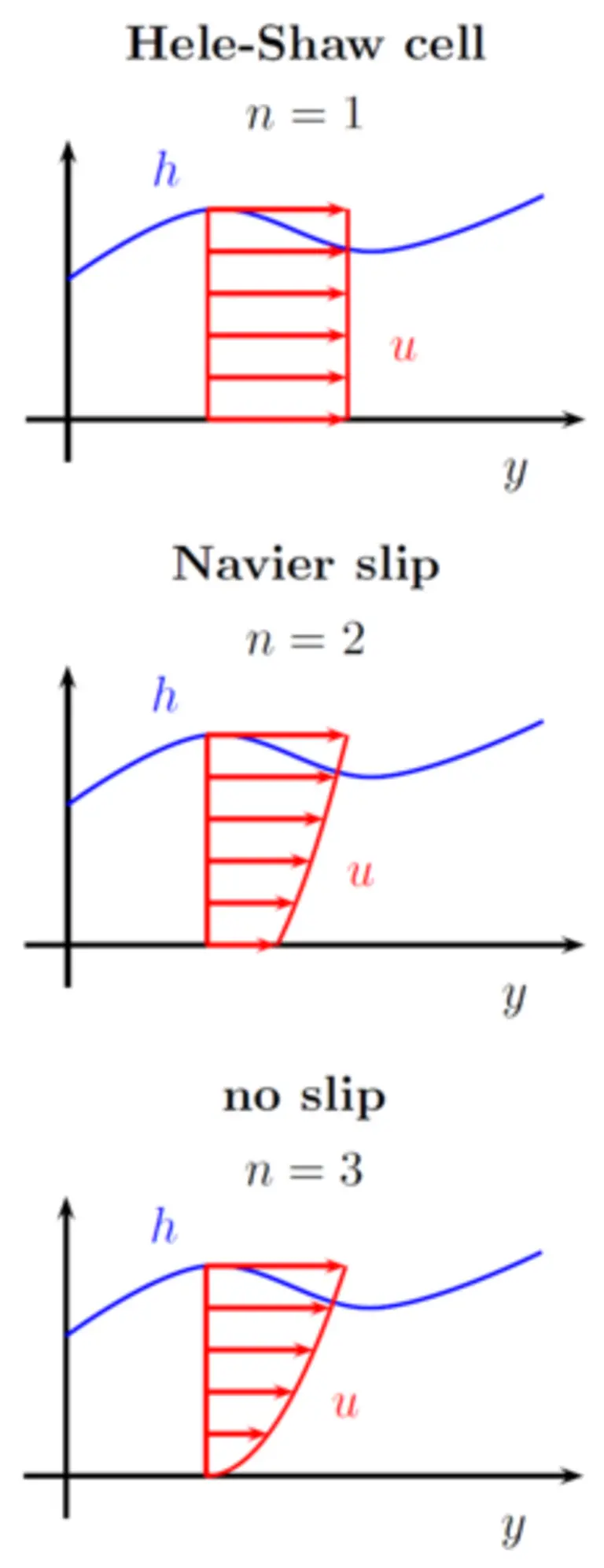

The resulting partial differential equation is a fourth-order degenerate-parabolic equation that - for a

where

The thin-film equation as a free boundary problem

Equation (1) is a fourth-order equation with a moving (free) boundary, that is, 3 boundary conditions are needed:

-

- One can also view equation (1) as a continuity equation, that is,

Often one assumes that the film height

where

Weak solutions

The mathematical treatment of the thin-film equation started with the work of Bernis and Friedman [h] establishing existence of weak solutions in

Qualitative behavior of the free boundary

Rigorously analyzing the qualitative behavior of the contact line in solutions to the thin-film equation (2) poses significant mathematical challenges: For the porous medium equation

(with

(for certain

holds with

Our method for the derivation of lower bounds on free boundary propagation is not limited to the thin-film equation, but is flexible enough to be applied to other higher-order nonnegativity-preserving parabolic equations: For example, in the case of the so-called quantum drift-diffusion equation an adaption of our ansatz can be used to prove infinite speed of propagation [12].

Gradient Flow structure of the thin-film equation

t is well-known since [j] that the thin-film equation can be seen as the gradient flow of the surface energy with respect to a Wasserstein-type metric for all mobilities

we can think of its tangent space as

Identifying a tangent vector

we define a metric tensor by

One observes that the gradient flow with respect to this metric and the free energy

for

This insight was used to obtain a first existence result for weak solutions in the partial wetting regime [1], where an approximative time-discrete solution for time-step size

which is formally equivalent to the time-discrete gradient flow equation. Here

Well-posedness and regularity for the thin-film free-boundary problem

It appears natural to ask whether the introduction of slippage indeed removes the singular behavior at the contact line. This leads to the mathematical question of regularity of the solution at the free boundary. In fact, developing a regularity theory for degenerate-parabolic fourth-order equations is a relatively new field. For the thin-film problem (2) we refer to the works of Giacomelli, Knüpfer, and two of the group members [6,10,v,y,z], in particular addressing the case of

Apart from the applied point of view, there is also a theoretical interest in the questions detailed above, since before the analysis starting with [6], uniqueness results have not been available for (2). The existence results for weak solutions [h,i,k,o,q] always relied on a compactness argument since the control of the solutions at the free boundary was not strong enough to apply the contraction mapping theorem. Again it is the detailed understanding of the regularity at the free boundary that enables us to prove existence and uniqueness of solutions for short times or for initial data close to generic solutions (stationary, traveling waves, or self-similar solutions, see below).

There is another theoretical motivation for our analysis, coming from the porous medium equation (3). Here a well-developed existence and uniqueness theory is available [g,p,r], which, however, at least partially relies on the use of a maximum (or comparison) principle. Therefore it seems of interest to study which of the analysis does or does not transfer from the second-order to the fourth-order case. Although the works for the particular case

It is instructive to further simplify the problem (2) to the case in which the behavior of solutions is self-similar. This is in fact the generic large-time behavior of solutions with compact support [15,t]. Here, the PDE problem (2) reduces to the study of a boundary-value problem for a third-order nonlinear ODE. Jointly with Lorenzo Giacomelli, we are able to show that the solution is generically not smooth, even if the leading-order traveling wave is factored off [9]. Instead we are able to prove analyticity in two variables: Factoring off the traveling-wave profile, the solution is an analytic function in

Given the understanding for the source-type solution, we can also treat the general PDE problem (2) for the physical relevant case of quadratic mobility (

Currently our main interest lies in a deeper understanding of the full system including slippage, for which source-type self-similar solutions do not exist. Thus even simplified ODE models turn out to be mathematically subtle. In particular the traveling-wave solution has no explicit characterization and exhibits two asymptotic regimes. Close to the contact line the solution has a similar asymptotic expansion as the source-type self-similar solution in the scaling-invariant case (2), whereas in the interior of the droplet we observe another asymptotic regime known as Tanner's law [d,l]. Here we are able to show that Tanner's solution (which was found in the case of no-slip, i.e.

In future work we would like to investigate the lubrication approximation starting from solutions of the (Navier-) Stokes system with slippage. Such a rigorous lubrication approximation was indeed carried out by Giacomelli and one of the group members in earlier work for the particular case

Selected group publications

Lubrication approximation with prescribed nonzero contact angle

In: Communications in partial differential equations, 23 (1998) 11/12, pp. 2077-2164Variational formulation for the lubrication approximation of the Hele-Shaw flow

In: Calculus of variations and partial differential equations, 13 (2001) 3, pp. 377-403Droplet spreading : intermediate scaling law by PDE methods

In: Communications on pure and applied mathematics, 55 (2002) 2, pp. 217-254Rigorous lubrication approximation

In: Interfaces and free boundaries, 5 (2003) 4, pp. 483-529Coarsening rates for a droplet model : rigorous upper bounds

In: SIAM journal on mathematical analysis, 38 (2006) 2, pp. 503-529Smooth zero-contact-angle solutions to a thin-film equation around the steady state

In: Journal of differential equations, 245 (2008) 6, pp. 1454-1506Ostwald ripening of droplets : the role of migration

In: European journal of applied mathematics, 20 (2009) 1, pp. 1-67Optimal lower bounds on asymptotic support propagation rates for the thin-film equation

In: Journal of differential equations, 255 (2013) 10, pp. 3127-3149Regularity of source-type solutions to the thin-film equation with zero contact angle and mobility exponent between 3/2 and 3

In: European journal of applied mathematics, 24 (2013) 5, pp. 735-760On uniqueness of weak solutions for the thin-film equation

In: Journal of differential equations, 259 (2015) 8, pp. 4122-4171Behaviour of free boundaries in thin-film flow : the regime of strong slippage and the regime of very weak slippage

In: Annales de l'Institut Henri Poincaré / C, 33 (2016) 5, pp. 1301-1327Infinite speed of support propagation for the Derrida-Lebowitz-Speer-Spohn equation and quantum drift-diffusion models

In: Nonlinear differential equations and applications, 21 (2014) 1, pp. 27-50Upper bounds on waiting times for the thin-film equation : the Case of weak slippage

In: Archive for rational mechanics and analysis, 211 (2014) 3, pp. 771-818Well-posedness for the Navier-Slip thin-film equation in the case of complete wetting

In: Journal of differential equations, 257 (2014) 1, pp. 15-81Well-posedness and self-similar asymptotics for a thin-film equation

In: SIAM journal on mathematical analysis, 47 (2015) 4, pp. 2868-2902Relaxation rates for a perturbation of a stationary solution to the thin-film equation

In: SIAM journal on mathematical analysis, 48 (2016) 1, pp. 349-396Rigorous asymptotics of traveling-wave solutions to the thin-film equation and Tanner's law

In: Nonlinearity, 29 (2016) 9, pp. 2497-2536References

H. K. Moffatt. Viscous and resistive eddies near a sharp corner. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 18:1–18, 1 1964.

Chun Huh and LE Scriven. Hydrodynamic model of steady movement of a solid/liquid/fluid contact line. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 35(1):85–101, 1971.

Elizabeth B. Dussan V. and Stephen H. Davis. On the motion of a fluid-fluid interface along a solid surface. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 65:71–95, 8 1974.

L H Tanner. The spreading of silicone oil drops on horizontal surfaces. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 12(9):1473, 1979.

Michel Chipot and Thomas Sideris. An upper bound for the waiting time for nonlinear degenerate parabolic equations. Trans. Amer. Math. Soc., 288(1):423–427, 1985.

P. G. de Gennes. Wetting: statics and dynamics. Rev. Mod. Phys., 57:827–863, Jul 1985.

Sigurd Angenent. Local existence and regularity for a class of degenerate parabolic equations. Math. Ann., 280(3):465–482, 1988.

Francisco Bernis and Avner Friedman. Higher order nonlinear degenerate parabolic equations. J. Differential Equations, 83(1):179–206, 1990.

Elena Beretta, Michiel Bertsch, and Roberta Dal Passo. Nonnegative solutions of a fourth-order nonlinear degenerate parabolic equation. Arch. Rational Mech. Anal., 129(2):175–200, 1995.

R. Almgren. Singularity formation in Hele-Shaw bubbles. Phys. Fluids, 8(2):344–352, 1996.

A. L. Bertozzi and M. Pugh. The lubrication approximation for thin viscous films: regularity and long-time behavior of weak solutions. Comm. Pure Appl. Math., 49(2):85–123, 1996.

B.R. Duffy and S.K. Wilson. A third-order differential equation arising in thin-film flows and relevant to tanner’s law. Applied Mathematics Letters, 10(3):63 – 68, 1997.

Alexander Oron, Stephen H. Davis, and S. George Bankoff. Long-scale evolution of thin liquid films. Rev. Mod. Phys., 69:931–980, Jul 1997.

Michiel Bertsch, Roberta Dal Passo, Harald Garcke, and Günther Grün. The thin viscous flow equation in higher space dimensions. Adv. Differential Equations, 3(3):417–440, 1998.

Roberta Dal Passo, Harald Garcke, and Günther Grün. On a fourth-order degenerate parabolic equation: global entropy estimates, existence, and qualitative behavior of solutions. SIAM J. Math. Anal., 29(2):321–342 (electronic), 1998.

P. Daskalopoulos and R. Hamilton. Regularity of the free boundary for the porous medium equation. J. Amer. Math. Soc., 11(4):899–965, 1998.

Roberta Dal Passo and Harald Garcke. Solutions of a fourth order degenerate parabolic equation with weak initial trace. Ann. Scuola Norm. Sup. Pisa Cl. Sci. (4), 28(1):153–181, 1999.

Herbert Koch. Non-Euclidean singular intergrals and the porous medium equation. Habilitation thesis, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg, 1999.

Roberta Dal Passo, Lorenzo Giacomelli, and Günther Grün. A waiting time phenomenon for thin film equations. Ann. Scuola Norm. Sup. Pisa Cl. Sci. (4), 30(2):437–463, 2001.

J. A. Carrillo and G. Toscani. Long-time asymptotics for strong solutions of the thin film equation. Comm. Math. Phys., 225(3):551–571, 2002.

Roberta Dal Passo, Lorenzo Giacomelli, and Günther Grün. Waiting time phenomena for degenerate parabolic equations - a unifying approach. In Geometric analysis and nonlinear partial differential equations, pages 637–648. Springer, Berlin, 2003.

Lorenzo Giacomelli and Hans Knüpfer. A free boundary problem of fourth order: classical solutions in weighted Hölder spaces. Comm. Partial Differential Equations, 35(11):2059–2091, 2010.

Hans Knüpfer. Well-posedness for the Navier slip thin-film equation in the case of partial wetting. Comm. Pure Appl. Math., 64(9):1263–1296, 2011.

Hans Knüpfer. Well-posedness for a class of thin-film equations with general mobility in the regime of partial wetting. preprint, 2012.

Hans Knüpfer and Nader Masmoudi. Darcy flow on a plate with prescribed contact angle - well-posedness and lubrication approximation. preprint, 2012.

Hans Knüpfer and Nader Masmoudi. Well-posedness and uniform bounds for a nonlocal third order evolution operator on an infinite wedge. Comm. Math. Phys., 320(2):395–424, 2013.

Presentations

- Logarithmic correction to droplet spreading rate because of Navier slip regularization (see PS, 222 Kbyte)

- Short-time existence theory of smooth solutions based on linear theory (see PDF, 1.1 Mbyte)

- Towards a regularity theory for the moving contact line (see PDF, 289 Kbyte)